Pearl® Laser

Pearl® LaserThe Ultimate Guide To U.S. Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Regulation, Part I

In part one of this series, we’re examining the early history of the FDA, and the events that contributed to the past and present of American food, drug, and cosmetic policy.

Whether we’re strolling through Sephora, standing in line at the pharmacy, or tackling an online Target run, we tend to take for granted that the items in our basket — from makeup and personal care products to prescription and over-the-counter medications — are safe and effective. The same holds true for the cosmetic treatments and plastic surgery procedures recommended to us by medical professionals.

Thanks in large part to consumer protection laws and regulations in the United States, this is (mostly) a fair assumption. But that wasn’t always the case. In this two-part series, we are looking closely at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA): the people, products, and events contributing to the past, present, and future of American food, drug, and cosmetic policy.

Land of the Free, Home of the Huckster

It’s almost inconceivable for us to imagine a world without Starbucks and self care. But back in the early years of the founding fathers, most Americans rarely bathed. They grew what they ate and had limited methods of food preservation. ‘Basics’ like soap and tooth powder weren’t widespread until the mid-nineteenth century.

Because the accepted standards of ‘medical care’ (hello, bloodletting?) were so scary, many Americans did not trust traditional doctors. This created the opportunity for the rise of patent medicines: concoctions that purported to alleviate or cure any number of ailments with little or no scientific basis.

So-called quack remedies hawked by traveling ‘snake oil’ salesmen (named for the supposedly exotic ingredients in their formulas) had equal potential to cure or kill. Enterprising patent medicine entrepreneurs were among the first American marketers to employ advertising tactics like testimonials and celebrity endorsements to convince the unsuspecting public.

The Earliest Days of U.S. Food & Drug Policy

In 1813, the fledgling federal government passed the Vaccine Act to ensure a central, reliable supply of smallpox vaccine existed to combat one of the world's deadliest diseases. It was the first law passed by Congress that addressed the health of Americans. Nine years later, the law was repealed after a vaccine mixup resulted in several deaths. The incident stoked Americans’ distrust of traditional medicine.

A group of physicians met in Washington in 1820 to address the scary reality that many ‘medicines’ of the time were deadlier than the ailment they were meant to cure. Together they developed the U.S. Pharmacopeia — the first set of guidelines for medicine quality. Following these standards was, however, not obligatory.

Welcome to the Jungle

By the mid-1800s, the Industrial Revolution began changing the consumer landscape. Factories mass produced food, clothing, and household items that could be shipped via the new railroads that were crisscrossing the country. Goods that were previously available only to the wealthy and elite became more readily available.

But, without any oversight, food and drug contamination was rampant. Consumers had no way of knowing whether the canned beef stew they bought was really even beef or, worse, if eating it would lead to a deadly case of food poisoning. In 1906, Upton Sinclair published The Jungle, a shocking exposé of the appalling conditions of meatpackers in Chicago. His descriptions of tainted, rotten meat fueled public outrage over the unscrupulous practices of food industry manufacturers.

Is the Cure Worse Than the Disease?

Even if a food, drug, or cosmetic manufacturer had no ill intent, the lack of research and scrutiny allowed plenty of unsafe products to flourish into the early twentieth century. Cocaine toothache tablets and heroin cough syrup (say what?) were just two of the remedies marketed to treat children.

With the amount of information now available at our fingertips, it’s hard to imagine falling victim to sensational medical claims and false advertising. Here’s a look at some of the popular (and dangerous!) turn-of-the-century quack medicines and devices that misled unsuspecting consumers:

Vapo-Cresolene

Vapo-Cresolene was touted as a cure for respiratory conditions ranging from sneezing to asthma and whooping cough. In reality, it was vaporized coal tar. The packaging instructed users to heat the tar in an enclosed room throughout the night, which led to poisoning in children from inhaling the toxic fumes. Vapo-Cresolene was one of the many ways companies sought to profit from the waste products of burgeoning industries.

Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup

First introduced in 1849 and widely marketed in the U.S. and U.K. as a cure-all for fussy babies, Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup was mostly a mix of morphine and alcohol. According to the company’s advertising lore — meant to gain a mother’s trust — “Mrs. Winslow” was allegedly a nurse who developed the formula. The suggested dosage of six to 10 drops for infants lulled them to sleep, but it’s estimated that thousands never woke up. Because there were no labeling requirements, mothers had no way of knowing that one teaspoon of syrup (recommended three to four times daily for babies six months and up) contained a lethal dose of morphine.

Liquozone

Billed to the public as “liquid oxygen,” Liquozone was a mixture of water and sulphuric and sulphurous acids, with traces of hydrochloric or hydrobromic acid. It’s inventor capitalized on the public’s ignorance and the widespread, mistaken belief that ozone gas has a purifying effect. Taking advantage of emerging germ theory, the manufacturer touted the liquid’s supposed antibacterial qualities, curing everything from ‘bowel troubles’ to cancer. The company was eventually discredited in court, though potentially dangerous ozone ‘purification’ devices are still being marketed today.

The Pure Food and Drug Act

Public outcries over the widespread sickening and death of consumers, combined with the sensation caused by The Jungle, led the government to take action. In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln created the Bureau of Chemistry under the Department of Agriculture (USDA). In 1880, its chief chemist, Peter Collier, advocated for a federal food and drug law. Though the bill was defeated, more than 100 food and drug bills were introduced in Congress over the next quarter century.

Collier’s successor, Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, continued to campaign for legislation. He is known as the “Father of the Pure Food and Drugs Act,” which passed Congress in 1906 and was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt. According to the FDA, the law “prohibits interstate commerce in misbranded and adulterated foods, drinks and drugs.” The Meat Inspection Act was passed the same day. In 1907, the USDA issued a list of seven chemical colors considered suitable for use in foods. Notably absent from the law, however, were provisions for drug and cosmetics safety.

Early Challenges to the PFDA

Patent medicine manufacturers were quick to contest the new regulations (and expose loopholes) of the Pure Food and Drug Act. After the government seized large quantities of a useless ‘remedy’ called Johnson's Mild Combination Treatment for Cancer, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the manufacturer in U.S. v. Johnson (1911). The court declared that the act “does not prohibit false therapeutic claims but only false and misleading statements about the ingredients or identity of a drug.”

In response, Congress enacted the Sherley Amendment in 1912, which made it illegal to label medicines with false therapeutic claims but stipulated that there must be an intent to defraud in order to convict (which proved to be very difficult to accomplish in court). In 1913, the Gould Amendment required food packages to be clearly labeled “in terms of weight, measure, or numerical count” on the outside. The following year, the Harrison Narcotic Act began requiring prescriptions and record keeping for narcotics.

Also in 1914, the Supreme Court ruled on food additives, deciding that the government must show that a chemical additive caused harm before the substance could be banned. In other words, just because a food contained a hazardous chemical, didn’t mean it was illegal. Because there were no codified safety standards, the government had to prove all over again — in every case — that a substance was hazardous.

The Takeaway

These early steps toward regulating food, drugs, and cosmetics in America were crucial in the quest to protect people from the hazards of tainted and dangerous goods. Fortunately for U.S. consumers, it was only the beginning. Stay tuned for our second installment of this story, where we’ll explore the modern FDA — from its Great Depression-era origins to its relevance today.

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

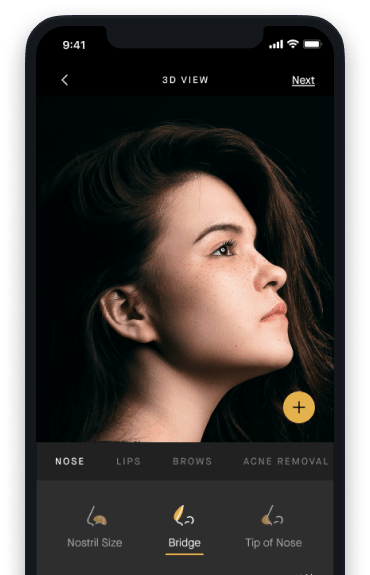

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.