Ablative Erbium Laser

Ablative Erbium LaserThe Ultimate Guide To U.S. Food, Drug, And Cosmetic Regulation, Part II

In part two of this series, we’re examining the more recent history of the FDA, and the events that contributed to the past and present of American food, drug, and cosmetic policy.

In the early twentieth century, unsuccessful federal court cases and continued adverse consequences of unsafe food, drugs, and cosmetics quickly illustrated the inadequacies of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. As we discussed in part I of this series, the law did provide some safety standards and labeling accuracy, but it also required that the government prove a manufacturer intended to defraud with its labeling — a nearly impossible burden to meet.

The law also had no power to regulate cosmetics, medical devices, or advertising, nor did it create any standards for food safety. Among the tricks and bad practices used by manufacturers:

- Glass bottles that only appeared to be full

- False-bottomed boxes

- Misleading and fraudulent advertising claims

- Inadequate record keeping for prescription drugs

- A lack of safety testing for new drugs and cosmetics

Consumer advocacy groups and the publication of books like Arthur Kallet and F.J. Schlink's 100,000,000 Guinea Pigs: Dangers of Everyday Food, Drugs and Cosmetics (1933) raised awareness of the law’s shortcomings, but the offenses continued.

The American Chamber of Horrors

In 1933, the chief education officer (Ruth deForest Lamb) and chief inspector (George Larrick) of the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) assembled a collection of misleading and dangerous products to illustrate the inadequacies of the current laws and to advocate for broadened regulatory powers. The exhibit gained notoriety when Eleanor Roosevelt toured it with a reporter, who dubbed the collection the “Chamber of Horrors.”

Included in the exhibit (which was a sensation at the Chicago World’s Fair) were a variety of packaging tricks, advertising swindles, and products that didn’t work or, worse, were hazardous and toxic. Some of the highlights:

- Lash Lure: The toxic aniline eyebrow and eyelash dye that caused serious infections, blindness, even death among salon-goers.

- Banbar: A blend of alcohol, water, and horsetail (a weed) flavored with peppermint purported to treat diabetes that actually killed those who relied on it instead of insulin.

- Bred-Spred: A line of enticingly packaged ‘jams’ that contained artificial colors and flavors, pectin, and hayseeds but no fruit.

- Koremlu: Billed as a harmless hair removal cream, this toxic concoction contained thallium acetate and caused systemic hair loss and neurological damage.

The Elixir of Sulfanilamide Disaster

As a result of mounting evidence and pressure, a bill to revise and expand the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 was introduced before Congress in 1933. But passage of the bill was stalled for years as politicians, advocacy groups, and lobbyists debated. In 1937, a Tennessee manufacturer created what was believed to be a red raspberry-flavored liquid version of sulfanilamide, a true ‘wonder drug’ that had proven to be safe and effective (in powder form) to treat strep infections. After the elixir was tested for flavor, appearance, and fragrance, it was shipped to doctors and pharmacies across the country.

Elixir Sulfanilamide killed 107 people, many of them children, because the sweet liquid was, in fact, a solution of the powdered drug and diethylene glycol — a chemical commonly used as antifreeze and documented at the time to be a deadly poison, though the manufacturer hadn’t bothered to check.

The combined efforts of the FDA, physicians, and media saved countless more deaths. But, due to the limitations of the 1906 law, the FDA was only able to prosecute the S.E. Massengill Co. because it had mislabeled its product an “elixir” (which must contain alcohol) instead of a “solution.” The fact that the formula contained a deadly poison was not legally actionable.

Finally: The Food, Drug & Cosmetics Act of 1938

The Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster provided the final incentive Congress needed to act. In 1938, the Food, Drug, and Cosmetics Act was passed, making it illegal to market unsafe drugs, cosmetics, and devices, establishing food safety standards, and requiring that a drug be proven safe prior to marketing. Factory inspections and court injunctions were also added to the FDA's arsenal.

In the ensuing decades, court cases and congressional acts bolstered the original FD&C Act. The highlights:

- Wheeler-Lea Act (1938): Empowered the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to regulate drug, device, and cosmetic advertising.

- “The Black Book” (1949): A guide to evaluate the safety of chemical food additives that was updated in 1982 to include color additives and is now known as “The Red Book.”

- Durham-Humphrey Amendment (1951): Defined what drugs require a prescription from a licensed practitioner

- Miller Pesticide Amendment (1954): Established procedures for setting safe pesticide limits on agricultural products (this is now handled by the Environmental Protection Agency).

- Food Additives Amendment (1958): Prohibited use of cancer-causing substances and required new food additives to be proven safe prior to marketing.

- Color Additive Amendment (1960): Prohibited use of cancer-causing color chemicals in food, drugs, and cosmetics, and required manufacturers to first establish safety before use.

- Kefauver-Harris Drug Amendments (1962): Required manufacturers of new drugs to prove effectiveness to the FDA.

- Federal Anti-Tampering Act (1983): Passed in response to cyanide poisoning from tainted Tylenol, it made it a crime to tamper with packaged consumer goods.

- Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (1990): Required all foods to have standardized labeling.

- Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (2009): Gave the FDA authority to regulate tobacco products.

- Drug Quality and Security Act (2013): Passed in response to a deadly meningitis outbreak in 2012 originating from a compounding pharmacy, it required greater oversight and electronic prescription drug tracing.

Drugs vs. Cosmetics, According to the FDA

After generations of federal oversight, most people today are familiar with the FDA. From lettuce recalls to Botox® approval, the agency affects our lives on a daily basis. But, in spite of its notoriety, many Americans aren’t clear about how the FDA regulates cosmetics and beauty products in this country. “If you ask 10 different people, then you will get 10 different answers,” says cosmetic chemist Ni’Kita Wilson.

Here’s where the definitions spelled out in the FD&C Act become important:

- Drugs: “Articles intended for use in the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease” and “articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body of man or other animals.” (e.g. oral contraceptives and the active ingredients in sunscreen)

- Cosmetics: “Articles intended to be rubbed, poured, sprinkled, or sprayed on, introduced into, or otherwise applied to the human body… for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering the appearance.” (e.g. moisturizer, lipstick, hair color)

Some products meet the definition of both a drug and a cosmetic. These include things like dandruff shampoo (shampoo is a cosmetic but controlling dandruff alters bodily function like a drug) and most toothpaste (tooth cleanser is a cosmetic but added fluoride is a drug).

So, how does the FDA influence the creation of skincare and makeup? “When we're developing acne, sunscreen, or other over-the-counter products, we have to adhere to the ‘rules of engagement’ outlined in the monograph ‘rule book’ for that category,” Wilson explains. “I have to be careful with the benefit claims of each product that I develop to ensure that I am not misleading the consumer to think that my cosmetic product has drug benefits.” For example, there are certain colorants that she can’t use on the lip or eye area as per the FDA. “They definitely have a say in how things are done,” she notes.

The Difference Between FDA Approval & FDA Regulation

The FD&C Act and ensuing laws gave the FDA the power to regulate food, drugs, cosmetics, and medical devices.

- FDA Regulation: Implies the agency legally oversees those industries — setting rules, guidelines, and standards and enforcing compliance with relevant laws.

- FDA Approval: Signifies a product has been proven safe and effective through research and clinical trials prior to its market release.

Drugs (both prescription and over-the-counter) must either obtain FDA approval or meet strict standards called ‘monographs’ prior to being marketed. With the exception of color additives, cosmetic products and ingredients do not need FDA approval, nor do they need to be registered with the FDA like drugs and drug manufacturers do.

Falsely claiming that a product is “FDA approved” may be a federal offense. Here’s a rundown of what the U.S. Food and Drug Administration does and does not approve:

The FDA Does Approve:

- New drugs and biologics (like vaccines and blood products)

- Medical devices (via a tiered clearance system)

- Human cells and tissues (through a risk-based approach)

- Food additives

- Color additives used in FDA-regulated products

- Animal food additives and drugs

The FDA Does Not Approve:

- Companies

- Compounded drugs

- Tobacco products

- Cosmetics

- Medical foods

- Infant formula

- Dietary supplements

- Food labels/nutrition facts

- Structure-function claims (like “calcium builds strong bones”)

FDA Recall vs. FDA Withdrawal

So, what happens when a product is deemed unsafe, contaminated, or questionable? In cases of minor violations that wouldn’t involve legal action, the FDA requests a so-called ‘market withdrawal.’ The company isn’t in trouble per se, but they’re being asked to remove the product from distribution until the correction is made.

On the other hand, the FDA recalls a product when there’s a clear legal violation. Goods are removed from distribution and consumers are advised to either return or dispose of the product. Recalls are divided into three categories:

- Class 1: Product could cause serious harm or death

- Class 2: Product can cause temporary or reversible health consequences

- Class 3: Not likely to cause harm but still a violation

It’s estimated that over 4,000 drugs and devices are recalled each year.

The Push for Cosmetic Regulation

The FD&C Act of 1938 does not require cosmetics manufacturers to register (it’s voluntary), and they are not obligated to follow Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) the way drug companies are. Under current law, the FDA has no authority to recall cosmetics — the agency can only request that a manufacturer voluntarily recall a product. If a cosmetic manufacturer is making claims reserved for drugs or if their ingredients are found to mimic drugs, then the FDA can step in, as they’ve done with several lash serum makers over the past decade.

The need for cosmetic regulation came to a head in 2019 with the revelation that Johnson & Johnson concealed for decades that the talc in their baby powder could be contaminated with asbestos. The problem arose again with tween accessories giant Claire’s when it refused to recall several makeup products that independently tested positive for asbestos. Instead, it opted to withdraw the items from shelves while reassuring the public that its makeup is safe.

Currently, Congress is considering two bills that would expand the FDA’s authority over cosmetics. The Cosmetics Safety Enhancement Act of 2019 would require manufacturers to establish product safety and report adverse effects, while empowering the FDA to conduct its own cosmetic safety testing. The Safe Cosmetics and Personal Care Products Act would require that all ingredients (including the notoriously-vague ‘fragrance’) be detailed on labels and would ban all toxic ingredients.

Safety & Efficacy

Given that many consumer goods are not expressly approved prior to marketing, we’re generally left to trust that the manufacturers are following good practices and that the market will weed out those who aren’t. After all, it’s in a company’s best interest to meet its claims.

However, there are plenty of examples of dangerous products being marketed and widely used before the FDA stepped in (hello, tobacco). So, how skeptical should we be before purchasing? “In general, I would presume a large majority of the products to be safe,” Wilson says. “Read the ingredient label to see if the product contains ingredients that don't raise any red flags.”

If you’re not sure about an ingredient, do some research. “Paula's Choice has a helpful ingredient dictionary based on relevant studies,” Wilson suggests. Another tip? Keep your sources varied. “Read all types of information — not just those stating that everything is toxic,” she cautions.

What about ‘green,’ ‘clean,’ ‘vegan,’ or ‘organic’ beauty products? We’ve talked about green beauty recently, but in terms of FDA regulation, these terms are simply buzzwords. “The only term that has a true meaning tied to it is ‘organic,’ which is attached to the USDA,” Wilson explains. “The FDA does not recognize any of the others. They are just marketing terms and are no indication of the product’s safety profile or if it's better than another product.”

The Takeaway

While the FDA has certainly made the consumer landscape — including the beauty business — safer and more efficacious, it’s still up to us to do our homework before making cosmetics and personal care choices. With consumers demanding more transparency than ever from brands and manufacturers, it seems like only a matter of time before the laws evolve again.

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

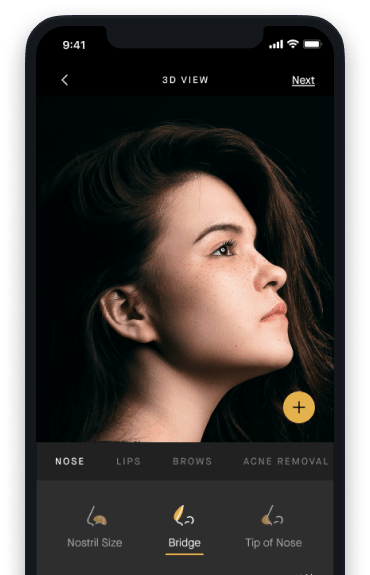

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.