Periorbital Botox for Crow's Feet

Periorbital Botox for Crow's FeetCan You Become Immune To Botox?

Even if you’re diligent about staying on top of your appointments, is it possible to become less responsive to neurotoxins and see fewer results over time? All signs point to yes — but it’s complicated.

There’s no question that Botox® and its fellow neurotoxins (hi, Dysport®, Jeuveau®, and Xeomin®) are among the most efficacious and popular non-surgical wrinkle reducers in aesthetic medicine. Botulinum toxin type-A (BoNT-A) has come a long way since its accidental cosmetic discovery by ophthalmologist Jean Carruthers, MD, and her dermatologist husband Alastair Carruthers, MD, in 1987. The couple noticed a smoothing and anti-wrinkle effect on the forehead of patients who were being injected with Botox® to treat uncontrollable blinking and eye spasms known as blepharospasm.

Fast forward to today, and the toxin has drastically advanced in terms of both its approved and off-label uses. The uses of Botox® and its competitors are seemingly endless. They have been used to address everything from minimizing crow’s feet and migraines to slimming the jawline and reducing the amount of sweat your body produces with little to no downtime and minimal pain (the injection feels like a pinprick).

When it comes to lines and wrinkles, neurotoxins work by temporarily paralyzing muscles for cosmetic effect. By injecting BoNT-A into areas where repeated muscle contractions occur (think: in-between the middle of the eyebrows, the outer corners of the eyes, and the forehead), the lines, folds, and furrows that would normally etch themselves into the skin are softened. The results are not immediate — initial benefits start to be visible at the five-day mark, with full results at two weeks — and they don’t last forever. For most patients, Botox® and the like naturally degrades over the course of three to four months, which is why upkeep is essential.

But what if the effects of the wrinkle-reducer start to fade after only a few weeks? Or what if, after years of success, you are hardly seeing a result anymore? You may be resistant to Botox®, and we’re talking to experts to understand why.

What Is Botox Resistance?

Known as ‘Botox resistance,’ some patients may develop an immune response to Botox® that reduces the effectiveness of the treatment, says Steve Fallek, MD, a board certified plastic and reconstructive surgeon and medical director of BeautyFix MedSpa. “The protein complex in the product may stimulate neutralizing antibodies,” he explains.

While BoNT-A is the primary active ingredient in cosmetic neurotoxins, the exact formulation of each brand is unique. Botox® (a.k.a. onabotulinumtoxinA), for example, features a proprietary blend of protective proteins alongside inactive ingredients like human albumin (i.e. plasma proteins) and sodium chloride. As such, it’s not just Botox® that can stop working — the effect can occur with any injectable neurotoxin. “Therapeutic proteins, including the core neurotoxin found in all neuromodulators on the market today, can induce immunogenicity, or an unwanted immune response,” says Brian Biesman, MD, a board certified oculofacial plastic surgeon in Nashville, TN. “Yet, the critical factors for neutralizing antibody formation are not well characterized.”

Neurotoxin resistance is nothing new. There are scholarly publications dating back to 2013 referencing Botox® immunity and the potential for antibody formation in certain individuals, says John Layke, DO, a board certified plastic and reconstructive surgeon and co-founder of Beverly Hills MD. The first incidents came from medical uses of Botox®, which employs higher doses of the neuromodulator. “Usually, immunity is a very dose-dependent thing,” notes Paul Jarrod Frank, MD, a New York City-based board certified dermatologist. “For cosmetic uses, Botox® doses tend to be rather small, which is why it is not very common to develop a true immunity to the product.”

As Dr. Frank explains, there is a difference between actual resistance and patient satisfaction. “The development of antibodies causes true Botox® immunity,” he says. “However, many people claim to experience Botox® immunity because they symptomatically feel that Botox® — or another neuromodulator — does not do what it used to do.” This is especially common among those who have been going under the needle for years. “As we get older, some of the simpler cosmetic treatments become a law of decreasing return,” Dr. Frank shares. “Some people will assume that if things don't give the same effect at age 40 as they did for them at age 30, they are now immune to the product.” While the treatment may not be as effective, such patients are not immune. “That is a psychological thing and not so much of a true immunological antibody immunity,” he notes.

If the body does in fact develop antibodies, the patient will not see as dramatic of a result — or any result at all. “Actual immunity, when people get less sensitive to Botox®, is that the body responds with antibodies to the product,” Dr. Frank says. “Once those circulating antibodies are in the bloodstream, they will attach to the Botox® molecule.” So, as the immune system produces the antibodies, repeat injections of Botox® or other neurotoxins begin to become less active in the treated areas.

Unfortunately, the only way to tell if you are producing antibodies is with visible evidence (i.e. lack of results). Clinical trials released by Allergan (the manufacturer of Botox®) show that no more than 1.5 percent of patients develop any “neutralizing antibodies.” In short, only about one in 10,000 people have a natural resistance to the drug. “It’s an extremely rare phenomenon,” Dr. Biesman says. “I have been injecting for over 30 years and have seen very few true cases. Most often, the patients who feel they are non-responders require treatment of a different dose or distribution."

Why Botox May No Longer Be Working For You

Many patients use neuromodulators for decades with good results, and it is unclear what precisely about Botox® makes patients believe they are more immune to it than other toxins, Dr. Layke says. “Botox® is made of the active ingredient botulinum toxin A and other nontoxic complexing or binding proteins,” he explains. “Any one of these may induce an immune or ‘foreign’ response leading to antibody formation.”

Perhaps it’s less about the product and more about the patient. According to Dr. Frank, it’s not that the neuromodulator itself becomes less effective. Instead, we age and our anatomy changes, which limits our ability to get the effect that we want. “Neuromodulators are never going to be as effective on a patient who’s been using them for 20 years,” he shares. “That has less to do with the immunological aspect and more to do with the fact that we are fighting time and the muscles change, so the relaxation of the muscle doesn’t always give the same clinical effect.” In some patients, neurotoxins may begin to produce less desirable results. “As we get older, neuromodulators can cause an over-relaxation of the muscles and lead to adverse reactions, like flattening the eyebrows, weakening of the smile, and motion limitations,” he adds.

Every doctor we spoke to for this story agrees that there is no connection between injector technique and product storage and a lack of visible results. “Injections at more frequent intervals and higher doses may have an effect on immunogenicity, but this is such a rare phenomenon and impossible to study,” Dr. Biesman notes.

Besides developing toxin-inhibiting antibodies, it is also possible for the body to naturally metabolize the toxin at a faster-than-normal rate. “The normal amount of time it takes the body to metabolize Botox® ranges from two to four months,” Dr. Layke says. While no clinical data supports the claim, there are anecdotal reports that Botox® is shorter-lived in avid exercisers. If you’re someone who spins relentlessly on the Peloton bike and follows it up later in the day with a Pure Barre class, all that working out may be doing wonders for your body but little to no good for your wrinkles.

What to Do If Botox Is No Longer Working For You

Botox® isn’t the end-all, be-all when it comes to neuromodulators. Other toxins that are just as, if not more so effective are available. “If you feel that Botox® no longer gives you the results you want, I recommend trying an alternative neuromodulator,” Dr. Layke suggests. “Many times, patients that are unresponsive to Botox® see effective wrinkle reduction with Xeomin® or Jeuveau®.” Both of those and Dysport® work towards the same end goal of smoothing out lines and wrinkles. However, each contains a different molecular structure, so people may be sensitive to one and less to another.

Other types of ‘allergies’ to Botox® and the like can occur. A lot of times, this happens not due to the botulinum toxin type A but to the additive proteins or preservatives in the saline used. It’s all a matter of trial and error.

If the toxin route isn’t the right fit for you, filler may be an alternative. While neurotoxins and fillers are both injectables, it’s important to note that they do not act in the same way. Dermal fillers will not soften wrinkles where there is a loss of collagen in the skin. “They will not have the same effect as Botox®, but they can lift and create a rejuvenated look and feel,” Dr. Fallek explains.

Another possibility is a thread lift, which Dr. Fallek says “will not have the same effect as an anti-wrinkle injection, but they will lift and tighten loose, sagging skin tissues.” Other alternatives? Any treatment or procedure that improves wrinkles on the upper part of the face. “That could be getting your eyes done, a laparoscopic brow lift, or using fillers for fine lines in areas,” Dr. Frank shares. “It’s certainly best to always offer a patient several options if they see less efficacy from neuromodulators as they get older.”

Is It Time to Take a Botox Break?

Believe it or not, if there isn’t a viable solution that works for you, it might be time to take a bit of a Botox break. A pause doesn’t mean you can’t ever get Botox® (or another neurotoxin) again; it’s just that your body may need a hiatus from it. In some cases, a respite allows any remaining product to leave the body so that you can start from a clean baseline.

There are also rumors of a connection between zinc supplements and an increase in effectiveness in Botox®. While the jury is still out, an April 2012 clinical study in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology found that 92 percent of subjects supplemented with zinc 50 milligrams and phytase experienced an average increase in toxin effect duration of nearly 30 percent. Only time will tell if popping a few milligrams of the cold suppressant prolongs the life and betters the results of neurotoxin injections.

Until then, stick with what works for you, be it Botox®, a different neurotoxin, or another rejuvenation technique — as long as the results are evident enough for you, that’s what matters most.

All products featured are independently selected by our editors, however, AEDIT may receive a commission on items purchased through our links.

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

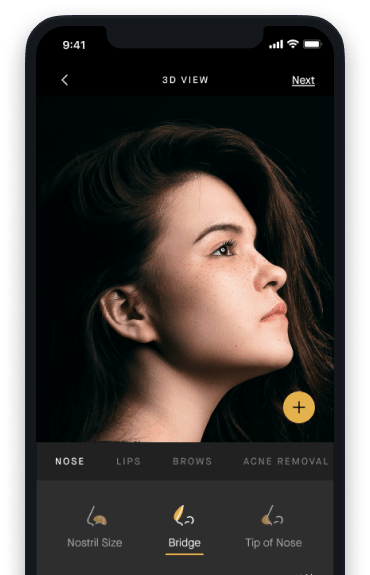

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.