Breast Augmentation with Fat Transfer

Breast Augmentation with Fat TransferHow To Treat And Prevent Fat Necrosis

The complication of fat grafting and breast reconstruction is not nearly as alarming as its name would lead you to believe.

We’re all privy to the risks associated with aesthetic procedures (think: infection, poor wound healing, additional complications), but few possible adverse effects sound as terrifying as fat necrosis. It feels as though nothing is lost in translation – ‘necro’ quite literally means death – so it’s easy to let your mind go, well, there. Now, before anybody spirals, it’s important to note that fat necrosis is not a life-threatening complication or a sign that you will be unable to recuperate. It is actually fairly straightforward to diagnose and manage, though it does have some implications. A complication most commonly associated with fat grafting procedures (including breast augmentation with fat transfer and Brazilian butt lift) and breast reconstruction, fat necrosis can occur anywhere on the body. In the event that it happens to you, The AEDITION is breaking down what to look out for and treatment options.

What Is Fat Necrosis?

To put it in layman's terms, fat necrosis is a collection of dead or damaged fat cells that have hardened and manifested as firm bumps. When the body has restricted oxygen flow as a result of surgery, radiation, or trauma, fat cells can die and release their contents to form a small body of liquified matter that hardens over time. “Fat necrosis usually appears as hard, firm lumps or, in some circumstances, as liquified fat,” explains Gregory A. Buford, MD, a board certified plastic and reconstructive surgeon in Lone Tree, CO.

The liquified fat (a.k.a. oil cysts) can also cause lumps. Oil cysts are fluid-filled sacs that feel smooth and squishy under the skin and can grow over time. Fat necrosis and oil cysts are different, though they are both the result of damage to the fatty tissue. As the tissue breaks down, it can harden into scar tissue or retain a more liquid composition.

Post-op, self-checks are recommended to observe any changes in the body, including lumps and bumps. Diagnosis of fat necrosis or oil cysts will require imaging technology, such as a mammogram, ultrasound, MRI, or, in some cases, a biopsy. For some, the only symptom of fat necrosis and oil cysts is the lump. Others may experience some discomfort in the area, skin that becomes thickened, bruised, or red, and/or aesthetic concerns from contour changes.

Due to the nature of the indicators, it’s common for breast surgery patients to rush to the conclusion that this is a sign of breast cancer – especially for those who’ve undergone reconstruction (with or without fat grafting). Despite their lumpy form, the American Cancer Society reports neither fat necrosis or oil cysts are cancerous nor increase the risk of cancer anywhere on the body. In fact, they are generally considered harmless.

What Causes Fat Necrosis

The roots of post-op side effects and complications often aren’t black and white, and this is no exception. “Fat necrosis can be caused by the lack of integration of transplanted fat into a specific area when specific areas of fat do not receive an adequate amount of blood supply,” Dr. Buford explains. Additionally, a patient’s post-op care lifestyle can play a role. “Necrosis can also result when too much pressure is placed on an area,” he continues. This is most common after a BBL. Fat necrosis “can be seen following a BBL if someone sits directly or applies direct pressure to the grafted fat too early after the procedure,” he shares.

Often, numerous factors need to be considered. The provider’s technique, the patient's ability to recuperate, and post-op care can all play a role in the occurrence of fat necrosis. “First, if extraordinarily large volumes of fat are grafted into any one area, this can potentially lead to less take of the fat and possible necrosis,” Dr. Buford says. “Next, how the fat is harvested and managed – both before and during transplantation – can also have a big effect on the potential for fat necrosis.”

Whether it’s occurring on the body or the face (think: autologous fat transfer in place of filler), these components aren’t mutually exclusive, so the root can be intra- or post-operative.

How To Prevent & Treat Fat Necrosis

The primary recommendations for preventing fat necrosis are to not smoke or be around those who do before or after surgery, as this restricts blood flow. For those who are post-BBL, follow your surgeon’s instructions for sitting and standing to a T. This should ensure you do not put too much pressure on the treatment area (if you’re curious, we have a recovery guide for that).

While complications can occur regardless of who performs the procedure, choosing a board certified plastic surgeon who specializes in the fat grafting procedure you are interested in can help mitigate risk. “I haven't seen a tremendous amount of variation in terms of potential for fat necrosis in specific areas of the body, but there is definitely a different threshold for the amount of potential for volume grafting in each area,” Dr. Buford notes. “As you can imagine, the buttocks handle far more fat than the breasts and the face.”

When it comes to treatment, options range from waiting it out to (in very rare cases) surgical removal. “Firm lumps resulting from fatty necrosis often resolve on their own or can be directly massaged to break them down,” Dr. Buford explains. “If contour changes are resulting from loss of this fat, then a second round of localized fat grafting can potentially be performed to fill in the gaps.” In the case of oil cysts, needle aspiration is usually able to drain the lump.

The Takeaway

For those who have had autologous fat transfer or breast reconstruction, fat necrosis is a risk. But it is one that is manageable and, in some cases, preventable. Arming yourself with the right information ahead of time will go a long way towards ensuring a smooth recovery and satisfactory outcome. “Fat is Mother Nature's filler and one of the earliest substances that plastic surgeons used to either smooth out contour deformities or add the desired volume,” Dr. Buford says. “Ultimately, results from fat grafting – when performed on the right patient, by the right surgeon, in the right area, and with the right amount – can produce very nice and very natural outcomes.”

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

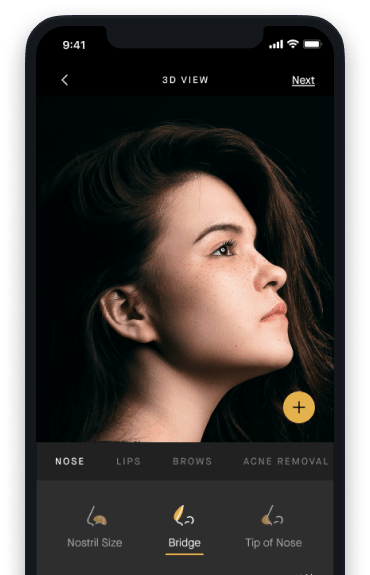

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.