Clear + Brilliant®

Clear + Brilliant®So, What Exactly Is Happening With Hydroquinone?

In recent months, the aesthetics industry has been abuzz with confusion over the impact of the CARES Act on hydroquinone. We’re breaking down everything you need to know.

In recent months, the aesthetics industry has been abuzz with confusion wondering: where did the hydroquinone go? The ‘gold standard’ treatment for hyperpigmentation has virtually disappeared from United States skincare shelves — an unwitting casualty of the 2020 CARES Act.

Yep, you read that right. The pandemic-inspired economic relief bill also contained a provision for modernizing the way the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates over-the-counter (OTC) drugs. The law reforms the agency’s notoriously cumbersome rulemaking system (in place since the 1970s) responsible for creating drug monographs — essentially rulebooks that OTC drug manufacturers can use to bypass the costly drug approval process. The CARES Act resolved all of the pending regulations that were stalled out by decades-old bureaucracy, declaring that “the most recently applicable proposal” would be considered final.

Problem is, the monograph for OTC skin bleaching products was still under review. Hydroquinone, which had initially been considered GRASE (read: generally recognized as safe), had been downgraded to ‘not GRASE’ in the most recent recommendation. Without a final monograph and a tentative categorization as unsafe, OTC hydroquinone was toast. Here’s everything you need to know about the compelling (and controversial!) history of hydroquinone in skincare.

What Is Hydroquinone?

Naturally found in a variety of plants (including coffee), hydroquinone was first distilled in 1820 and soon became one of the primary chemicals in photographic developing solutions. An antioxidant, it’s commonly used as a stabilizer in paints and motor fuels.

The skin bleaching properties of hydroquinone were discovered by accident in 1938 when a group of Chicago leather tannery workers sued the factory owner after they developed depigmented patches (a.k.a. leukoderma) on their hands and forearms. The patches corresponded to areas covered by factory-provided rubber gloves — which had been manufactured using a chemical called monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone.

In the following decades, researchers performed a variety of in vitro (i.e. test tube) and in vivo (a.k.a. animal or human) research using various concentrations and formulations of hydroquinone. They found the organic compound to be generally effective at reducing hyperpigmentation in both white and black test subjects — though the dark patches typically returned after discontinued use.

What Does Hydroquinone Treat?

Clinically, hydroquinone is used to treat dyschromia (read: skin discoloration or patches of uneven skin color). Variations include:

- Melasma: A symmetrical pattern of hyperpigmentation on the face caused by UV damage or hormonal changes.

- Solar Lentigines: Also known as sun spots or liver spots, they form when skin cells start to produce melanin as a result of repeated sun exposure.

- Freckles: Small dark spots, usually less than five millimeters in diameter, where skin cells have produced extra pigmentation.

- Post-Inflammatory Hyperpigmentation (PIH): Skin discoloration caused by inflammatory conditions like acne, burns, eczema, and dermatitis.

Hydroquinone’s most common use is in patients with PIH and melasma, while its chemical cousin — monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone — is FDA approved to treat severe cases of vitiligo.

Hydroquinone FAQs

More often than not, the more you learn about hydroquinone, the more questions you have. From dispelling common myths (i.e. hydroquinone equals bleach) to clearing up confusion (so, what’s the deal with FDA approval?), we’re breaking down some of the most frequently asked questions about hydroquinone.

1. Does Hydroquinone Bleach Skin?

Time for another biology lesson: When applied topically, hydroquinone has several effects on the skin cells that produce melanin. These melanocytes are found in the basal layer of the epidermis, where they produce eumelanin (brown or black pigments) and pheomelanin (yellow or red pigments). This process is facilitated by an enzyme called tyrosinase.

Hydroquinone impacts this phenomenon (known as melanogenesis) in a couple of ways:

- It inhibits DNA and RNA synthesis, altering melanosome formation

- It inhibits tyrosinase, which impedes melanogenesis

So, technically speaking, hydroquinone isn’t a bleach. Instead, it restricts the skin’s ability to produce melanin, which has the effect of lightening the complexion — but only while you’re using the medication.

2. What Are the Side Effects of Hydroquinone?

When used as directed, hydroquinone in concentrations up to 4 percent has relatively mild side effects. Common side effects include:

- Mild irritation

- Dryness

- Redness

- Inflammation

With that said, rare but serious side effects have also been documented. These include:

- Complete Depigmentation: Instead of just lightening the treatment area, the skin becomes devoid of pigment

- Leukoderma-en-Confetti: Splotchy areas of depigmentation dotted with spots of hyperpigmentation

- Exogenous Ochronosis: A skin disorder characterized by blue-black, caviar-like pigment deposits

It’s worth noting that there have been just 22 documented cases of exogenous ochronosis in the U.S. Worldwide, severe side effects are most commonly associated with prolonged usage of the drug against physician or labeling recommendations or when the hydroquinone is combined with dangerous ingredients like mercury.

3. Does Hydroquinone Cause Cancer?

Additionally, There have been quite a few studies trying to conclusively determine the safety of hydroquinone. Research from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the National Toxicology Program have provoked FDA concern. Here are the takeaways:

- Cancer: While there is some evidence that the drug — when taken orally — can lead to kidney cancer and leukemia in rats, no link has been found between hydroquinone use and cancer of any kind in humans.

- Fertility: Research examining the effects of hydroquinone on fertility and pregnancy in rats and mice have been inconclusive, but concerning enough to be noted by the FDA.

- Absorption: Hydroquinone has a relatively high absorption rate in humans, especially in certain formulations. This means that even though it is applied topically, somewhere around half of the drug enters the bloodstream.

4. Is Hydroquinone FDA Approved?

A deep dive into hydroquinone regulation in the U.S. reveals a little-known fact — not all drugs (even prescriptions!) sold in America are approved by the FDA. Let’s review how drugs are marketed:

- OTC: Over-the-counter drugs are typically regulated via what’s called a monograph — basically, the FDA’s rulebook for a class of drugs. Any OTC medication must comply with the monograph and does not need to go through the formal approval process. If the monograph is pending, an OTC drug can still be marketed in the meantime. This is why hydroquinone was available over the counter.

- Prescriptions: Prescription drugs can be approved (meaning they’ve gone through clinical trials and testing) or simply regulated. In the case of hydroquinone, there is only one brand-name product that’s FDA approved: Galderma Labs’ Tri-Luma. Because hydroquinone is approved for use in that medication, it’s included in the FDA’s Orange Book — a list of drug substances and their therapeutic equivalents (a.k.a. generic substitutes).

To bridge the gap between what’s clinically needed and what’s approved for prescribing, the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) allows compounding pharmacies to prepare and dispense drugs that haven’t been formally approved by the FDA. 503A compounding facilities produce drugs for individual patients on a case-by-case basis, while 503B facilities primarily supply bulk drugs for physicians to distribute in-office.

5. Did the CARES Act Ban Hydroquinone?

From 2006 to 2020, hydroquinone was in regulatory limbo. With no formal FDA ruling in place, the drug was readily available in both over-the-counter and prescription forms, including at strengths that exceeded the agency’s original recommendations.

Under the CARES Act, any drugs that were awaiting a final monograph and were deemed GRASE would be allowed to remain on the market without submitting a new drug application (NDA). Meanwhile, those drugs that did not have a final or tentative final monograph and were not considered GRASE (like hydroquinone) would be considered new drugs and required to submit an NDA within 180 days or face FDA enforcement.

The net net: all OTC hydroquinone had to be removed from the market. Manufacturers have the option to file for a new drug application, but the process is no joke. It’s estimated that the median cost of the application and approval process (including fees, clinical studies, etc.) is $19 million and can take about a year.

6. Can You Still Get Hydroquinone in the U.S.?

Understandably, many doctors are unclear about how the CARES Act impacts their ability to offer hydroquinone as a treatment option for patients with pigmentation concerns. “There really is no system in place or an alert that tells doctors ‘this is what you can, and cannot do,’” explains Allyson Avila, a partner at Gordon Rees Scully Mansukhani, LLP, and one of the country’s leading lawyers for the medical aesthetics industry. She advises doctors to contact their state drug regulators and/or an attorney for guidance.

Here is how Avila summarizes the law as it now stands:

“Currently, products containing hydroquinone can only be distributed if (1) they are approved by the FDA through the new drug application process or (2) the compounds are patient-specific prescriptions.

Hydroquinone remains a Category 1 substance on the FDA 503B Bulk Drug Substances List. Items that fall under Category 1 substances are under evaluation. Therefore, compounds that come from 503B facilities are not allowed to be dispensed at this time unless they are FDA approved. If these compounds are patient-specific prescriptions, they can be dispensed from either 503A or 503B facilities.

Additionally, each state has slightly different pharmacy regulations that go along with FDA guidelines. Physicians must comply with FDA regulations along with state and local pharmacy regulations before dispensing products and prescriptions containing hydroquinone.”

The Future of Hydroquinone in the U.S.

With so many patients relying on hydroquinone to treat hyperpigmentation, dermatologists and plastic surgeons alike are concerned about its continued availability. This is particularly true for BIPOC patients, who are often disproportionately affected by dyschromia.

With an FDA-approved formulation and inclusion on the Bulk Substances list for compounding, many experts feel it’s unlikely that the FDA will entirely remove hydroquinone from the U.S. market anytime soon. But the controversy surrounding the drug has spurred efforts to find safe and effective alternatives to treat hyperpigmentation.

A Brief History of Hydroquinone

- 1978: As the first step in creating an official monograph, an FDA advisory panel proposes recommendations for regulating skin bleaching products. Based on evidence presented, the panel suggests that hydroquinone be generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE) in concentrations of 1.5 percent to 2 percent and labeled to discontinue use after two months if no improvement is made.

- 1982: After public comments, the FDA proposes a tentative final monograph (TFM). The agency rejects an appeal from industry to allow concentrations up to 4 percent hydroquinone based on study findings showing no significant difference in efficacy between 2 percent and 4 percent. The FDA agrees with the panel’s conclusion that high concentrations of hydroquinone with exposure to the sun may cause disfiguring effects.

- 1999: The International Agency for Research and Cancer (IARC) determines that hydroquinone is not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans due to inadequate evidence in humans and limited evidence in experimental animals.

- 2001: The European Union bans OTC hydroquinone due to concerns about leukoderma-en-confetti and exogenous ochronosis.

- 2006: Based on additional research and data, the FDA decides to reverse its recommendation and proposes to classify hydroquinone as not GRASE, effectively withdrawing the tentative final monograph for the skin bleaching category. The agency cites “some evidence” of the drug’s potential link to cancer and fertility problems, as well as a clear link to exogenous ochronosis, even at low doses.

- 2011: Texas bans the sale of hydroquinone products in doctors’ offices but allows prescription sales to continue.

- 2017: FDA issues policy guidelines indicating that they do not intend to take action against facilities that compound Category 1 Bulk Substances (like hydroquinone) for prescription sale in doctors’ offices.

- 2020: CARES Act reforms the OTC monograph process, effectively outlawing non-prescription hydroquinone.

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

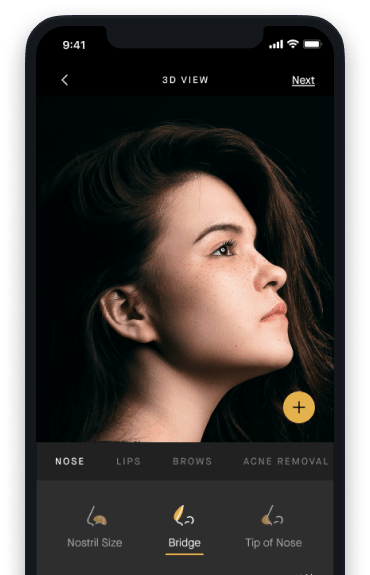

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.