Embrace® Scar Therapy

Embrace® Scar TherapyEverything You Need to Know About Mohs Surgery

This cutting edge skin cancer treatment will spare you a scare — and a scar.

Liz had a dry, scrape-like mark on her cheek that would occasionally bleed. The 44-year-old didn’t think much of it until she was having a facial and her aesthetician told her she thought the spot looked suspicious. Liz went to her dermatologist, who diagnosed her with one of the most common types of skin cancer, a basal cell carcinoma, and recommended Mohs surgery.

If you’re of a certain age and have logged a lot of time around the pool or on the tennis court sans sunscreen, there’s a good chance you’ve had a nonmelanoma skin cancer — or might develop one in the future. In fact, approximately one out of five people will get a nonmelanoma form of skin cancer (i.e. basal cell or squamous cell carcinoma) in their lifetime, according to research in JAMA Dermatology, and both types are linked to UV damage.

Since the head and neck tend to get the most sun exposure, it should come as no surprise that a study in the Indian Journal of Dermatology found that the majority of these suckers (basal cell carcinomas often take the form of transparent bumps, while squamous cells present more like sores or warts) pop up in those areas.

Cancer removal on the face can be a tricky business, with the standard operating process potentially resulting in some pretty disfiguring scars. That’s why dermatologists often recommend Mohs surgery (a.k.a. Mohs micrographic surgery). Named after Dr. Frederick Mohs, the surgeon who invented the technique back in the 1930s, the then-revolutionary, now-tried-and-true surgical procedure involves removing thin layers of cancerous tissue until only healthy skin remains.

“Mohs is always the number one option if you have a skin cancer on your face, or if you have a reoccurring one on another area of your body, or you have more than one skin cancer,” says dermatologist Cheryl Karcher, MD, the co-founder of the Center Aesthetic & Dermatology in New York City who performs Mohs surgery.

And, while Mohs is a common skin cancer surgery, it is important to note that it's a specialized procedure that not all dermatologists perform.

The Benefits of Mohs

The benefit of Mohs is that it allows the doctor to more precisely remove layers of skin containing the cancerous tissue because they are analyzing the results in real-time. By not disrupting as much of the healthy tissue around the cancer, the micrographic surgery is able to yield a more cosmetic result with minimal scarring, explains Dr. Karcher.

Ever heard the phrase "measure twice, cut once"? Well, in non-Mohs skin cancer treatment options, doctors basically do the opposite. They estimate the size of the cancerous area and cut generously around it to make sure they don’t leave any cancer cells behind. The biopsy is then sent out for examination post-surgery. The likely result? A large scar, which may not be a big deal if the cancerous lesion is, say, on your lower back.

More importantly, the procedure has a 98 percent cure rate, according to the Skin Cancer Foundation. And, while basal and squamous cell carcinomas are rarely life-threatening, “they can grow deeper and spread to other parts of the body, like the lymph nodes, which can be potentially deadly,” she warns. “So, it’s important to have them removed within 30 days of diagnosis.”

How Mohs Surgery Works

Mohs is an outpatient procedure done under local anesthesia. Patients sit back in a dentist office-type chair, the Mohs surgeon numbs them up, and then he or she excises a small tissue sample. “You don’t feel any pain,” says Joel, who opted for a Mohs procedure at age 60 to treat a basal cell carcinoma on his forehead.

After the initial layer of tissue is removed, patients step back out into the waiting room (with the surgical site bandaged so that they aren't, you know, sitting around with a gaping, bloody wound), while the doctor analyzes the sample under a microscope. Depending on how complicated the skin cancer happens to be, patients may wait for upwards of an hour as the doctor reviews the case.

If the surgeon determines the margins surrounding the cancer are clear (in other words, they got all of it out), the surgery is over. Piece of cake. But, more often than not, the margins aren’t clear, and the doctor will slice out more thin layers of tissue to analyze — and repeat the process until the results come back clear.

Liz, for instance, was done after two rounds, but Joel required four excisions. “The spot on my forehead was so small that I kept wondering why they were having to go back in again and again. But apparently, there was a lot of cancerous tissue underneath,” he says. “I was literally in the doctor’s office all day.”

Recovery After Mohs Surgery

Once the skin cancer has been successfully removed, the surgeon will close the wound with stitches. In Liz’s case, this part was fairly straightforward. After Mohs surgery, the doctor sewed her up, leaving her with a line of sutures running parallel to her nose. “I looked like I had been in a bar fight,” she jokes.

Joel’s surgery, meanwhile, left him with a silver dollar-sized hole in his forehead. “When the doctor handed me a mirror to look at it, it was breathtaking. I couldn’t imagine how they were possibly going to close this thing,” he recalls. Because the area was so large, his derm gave him the option of a skin graft, but he opted for traditional stitches instead.

While both Liz and Joel initially had to deal with a raw-looking mark (Dr. Karcher advises that stitches come out in 10 to 14 days but the area may remain red and swollen for another two weeks), their wounds were completely healed after one month. Today, neither of them have any visible scarring. “It’s pretty incredible,” Joel says.

Related Procedures

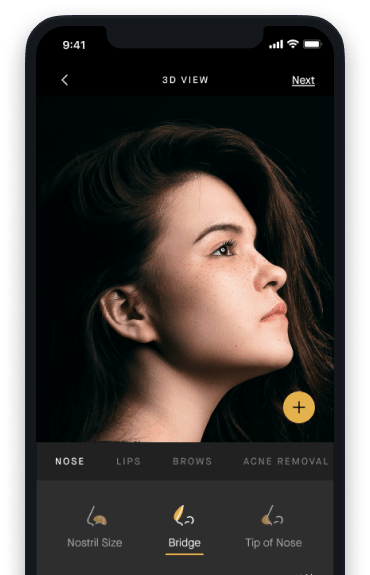

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.