Tummy Tuck (Abdominoplasty)

Tummy Tuck (Abdominoplasty)Why Don't More Women Become Plastic Surgeons?

Women make up the majority of cosmetic surgery patients. So, why don't more women become surgeons? Four female plastic surgeons lay out the factors they feel are contributing to the lack of gender diversity in the field.

In the spirit of Women's History Month and International Women's Day, we’re here to demystify the representation of women (or lack thereof) in plastic surgery.

It’s no secret that there are far fewer women than men in the field. A 2017 study from the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open found the female-to-male ratio of surgeons practicing plastic surgery is approximately one to five. The gap is smaller than other surgical specialities, but it is still surprising given that the American Society of Plastic Surgeon (ASPS) reports women received 92 percent of the cosmetic procedures performed in 2018.

Here, four top female plastic surgeons discuss their career progression and experience as women in aesthetic medicine. From family planning to finding mentors, they lay out the factors they believe contribute to the lack of gender diversity in the field.

Number of Women in Medicine vs. Plastic Surgery

New York City-based board certified plastic surgeon Nina Naidu, MD, attended Cornell University for medical school and graduated in 1997. “We were completely 50:50 — so 50 percent women — and we were one of the first classes to be evenly split,” she explains. In residency, however, Dr. Naidu was the only woman in her plastic surgery program. “When I did general surgery, there was one other woman out of eight,” Dr. Naidu remembers of her dual general and plastic surgery residency. “In plastic surgery, there were no women except for me in a group of six.”

For double board certified facial plastic surgeon Dara Liotta, MD, her medical school breakdown at Columbia University was over 50 percent percent women. When it came to residency, a much lower percentage of women chose to go into surgery or surgical subspecialties, like plastic and reconstructive surgery. “I completed a five-year residency in otolaryngology, head and neck surgery, which was nearly 50 percent female and then an advanced fellowship in facial plastics and reconstruction,” she shares. “In both residency and fellowship, the overwhelming majority of our teachers and attending surgeons were men.” Dr. Liotta said there were only four female attendings and over 30 male attendings during her residency and fellowship.

During her time at New York University School of Medicine, double board certified plastic surgeon Melissa Doft, MD, recalls an even proportion of women and men in her class. By the time she got to her surgical residency, however, the ratio of women to men was two to five. That split, she says, was actually pretty diverse compared to other programs. “Now the plastic surgery residency has one woman in a group of 13, so the ratio is one to 12,” she shares.

At Cornell Medical College, double board certified facial plastic surgeon Jennifer Levine, MD had a similar experience. In her class of 100 people, the ratio of male to female students was 55 to 45. “It was not until I started my surgical residency that I was the only woman out of 20 students,” she recalls, adding that she was surprised by the disparity. “I did not realize that there would be so few women, as I had not experienced that before,” she says.

Choice Between Motherhood & Plastic Surgery

One key reason many women choose not specialize in plastic surgery? The number of years the training involves. Not only does surgical residency usually last until residents are 32 or 33 (at the youngest), there is no real maternity leave involved.

“Residency occurs during the prime time that women are having children and starting a family. The work hours are grueling, expectations very high, and commitment paramount,” Dr. Doft says. “Unlike other residencies, like pediatrics or obstetrics, where there are many women, surgical residencies are not used to having women out for maternity leave and do not encourage it.”

While it varies by program, most offer four weeks of ‘medical leave’ (hardly enough for an actual maternity leave), and it can be extended by an additional two weeks using vacation time. Missing more than six weeks, however, will likely preclude residents from finishing the program on schedule. “If you try to take more time off, you might not be able to graduate on time,” Dr. Naidu says. “You might have to put extra time in, so that's a huge issue.”

Something else to consider? The lack of services available to new moms once they return to work. In addition to the grueling schedule of raising an infant while on-call and sleep deprived, finding a place to pump for women who choose to breastfeed may prove difficult. “There's a huge host of problems, so I think a lot of women look at that and think, ‘Wow this is just not compatible with having a regular life,’” Dr. Naidu says. “That's one reason there aren't that many women plastic surgeons.”

Yes, having children as a female plastic surgeon is difficult, but Dr. Liotta says there is rarely a convenient time for anyone to have kids. “Just have them and the world around you will adapt,” she says, adding that you’re not going to be able to be everything to everyone. “If you truly want to be a surgeon, and you can’t be happy doing anything else — you know who you are! — then say ‘F that’ and do it,” she advises. She recommends reaching out to other women for advice and support.

Additionally, Dr. Levine says small (but necessary) changes have been made to residency programs that allow for more of a work-life balance. “One week I was in the hospital 130 hours,” she recalls. Now, there are stricter rules regarding how many hours doctors can be at the hospital, and they are allowed to leave the hospital when they are post-call, she shares.

A Lack of Mentors for Women

In the generation ahead of Dr. Liotta, there were hardly any women specializing in plastic and reconstructive surgery despite the overwhelming majority of patients being female. “Perhaps this made it difficult for young women going through training to see a place for themselves in the field without obvious female mentors who had ‘been there and done that’ successfully in terms of navigating the predominantly male surgical culture and managing to balance work with family and outside life,” Dr. Liotta says. “Surgical residency and fellowship is very taxing, both emotionally and physically. For anyone — male, female, ethnic minority, ethnic majority — it is difficult to endure without seeing yourself in your mentors and having like-peers to confide and commiserate with.”

Dr. Naidu agrees, crediting her own mentor, Mia Talmor, MD, for her success. “Having a same-sex mentor has been shown to be extremely helpful for women plastic surgeons and for medical students who are considering going to the field,” she says. Dr. Talmor was the first female plastic surgeon appointed to the full-time faculty of Cornell University’s Weill Medical College in New York and was four years ahead of Dr. Naidu in school. “She is a very tough woman. She stands up for herself,” Dr. Naidu says, adding that Dr. Talmor is also extremely approachable.

Dr. Naidu connected with her when she was a first-year medical student, and the relationship continued from there. “I had that benefit that I had this role model way before I even applied for residency,” Dr. Naidu explains. “It was just something that was already there for me, and I think that made a huge difference for me.”

In general, some women may have been reluctant to go into these types of training programs because of the ‘boys club’ mentality, Dr. Levine says. But she thinks that perception is changing. “Women are no longer the only primary caregiver, and they may be the main breadwinner,” she says, adding that female patients are increasingly looking for a woman's perspective. “Whereas traditionally some women felt the need for male approval or a male voice, today’s women want to hear from someone like them and someone who understands and listens,” Dr. Levine explains.

Diversity in Plastic Surgery

The lack of diversity in plastic surgery isn’t just gender based. While a 2020 ASPS study showed there is a growing number of women entering plastic surgery residency programs, there is still a gender and ethnic disparity in the industry. “We treat the whole spectrum of patients, so there needs to be more diversity,” Dr. Naidu says. “We're still really ethnically underrepresented.”

Dr. Naidu is of South Asian descent, and, when she was in residency, she didn't know a single other South Asian plastic surgeon. “I didn't even see any until almost 10 years after I finished my training,” she says (yes, that’s male or female surgeons that were South Asian). “I didn't really see any ethnic diversity, until a good seven or eight years ago.” She notes that it's still not diverse per se, but it is starting to shift. “I notice it when I look around our conference room when I go to our monthly meeting for the hospital,” she says.

Dr. Levine notes that plastic surgery is only getting more popular and the patient population is increasingly diverse, but that is not necessarily reflected in the medical community. “In a patient population that is 90 percent women, only 10 percent of the surgeons are women,” Dr. Levine points out. “I personally try to change the ratio by mentoring other women through my medical school, my college, and other organizations such as Girls Inc and E-School for Girls.”

Providers should be able to show patients the breadth and diversity of their work, Dr. Doft adds. “Being based in Manhattan, I have the privilege to treat many different cultures. I think it is less important that patients see themselves in the provider and more that they see that the provider has treated other patients like themselves,” she shares. “For example, I am careful to select an array of different before-and-after photos, so that patients can find a patient who looks like them with regard to weight, proportions, and ethnicity.”

Advice to Aspiring Female Plastic Surgeons

First and foremost, Dr. Levine says to do what you love. “I think women today are more committed to lifting up other women and have less of the ‘I suffered so you can suffer too’ mentality,” she shares. In the last decade, Dr. Levine has noticed that “an increase in outspoken, talented, and feisty young women surgeons in conventional and social media have emerged as mentors for those who follow them.” That exposure will have a positive effect both immediately and long term. “I think that is being reflected in increasing numbers of women becoming plastic surgeons,” she says.

Dr. Doft encourages aspiring surgeons to focus on the life-changing impact cosmetic, plastic, and reconstructive work has on patients. “Every day I think that I am so lucky to have this job,” she says. “I have the opportunity to erase aspects of their bodies that women are self-conscious about and help them become more confident — and it only takes a few hours.”

While the progress has been slow, Dr. Naidu admits the profession has changed quite a bit over the years. When she completed her training 17 years ago and was just starting out, she was one of the few women in the space and was the only minority woman. “Now, there are a lot more women in the room,” she says. “It's more ethnically diverse as well, so it's really been a good shift.” Dr. Liotta is hopeful, too. “The road is long, and it’s definitely not the easy way,” she says. “But you can do it.”

More Related Articles

Related Procedures

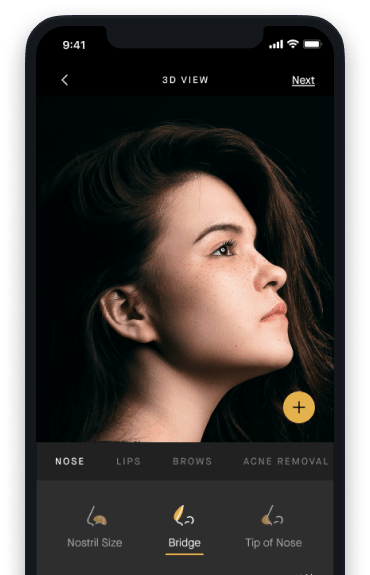

AI Plastic Surgeon™

powered by'Try on' aesthetic procedures and instantly visualize possible results with The AI Plastic Surgeon, our patented 3D aesthetic simulator.